Skin Deep

(Time Out, 1989)

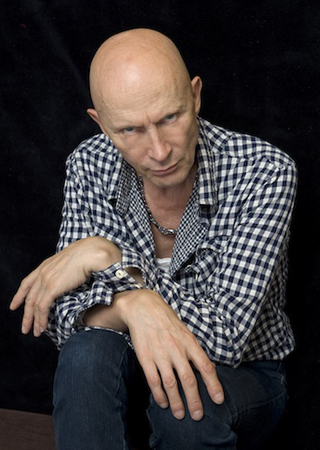

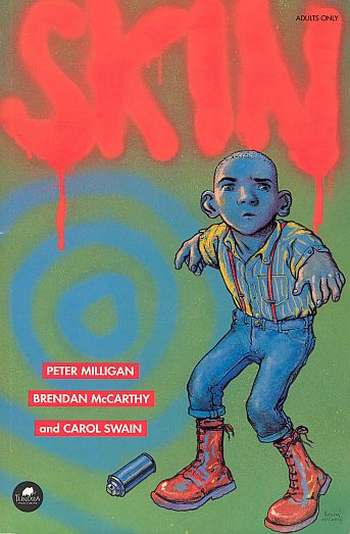

Skin (Peter Milligan, Brendan McCarthy & Carol-Swain)

In 1986, Watchmen, Dark Knight and Maus were all published. I was just starting out in journalism. This was to prove my “in”, my special subject that was trendy, timely, and about which I knew more than most. I wrote a number of comics features while at Time Out, before becoming editor, often to do with censorship. This was one: the stirring tale of Martin ’Atchet, thalidomide skinhead.

So we’re all agreed at last: an adult comic is not a contradiction in terms. Novelists Clive Barker and Iain Banks are starting to work with the medium, as is journalist Charles Shaar Murray; more pop stars than not read ‘2000AD’ (Madness named their record label Zarjazz after its catch-phrase, Wendy James wrote a song about one of its characters, Living Colour are seen reading a copy in their new video); other book publishers are following the Penguin lead in going graphic; and after ‘Batman’, new film adaptations are still pouring into production.

This week ‘2000AD’ is relaunching, together with its more political sister comic ‘Crisis’, as the 2000AD Group, complete with a bold new publishing and marketing strategy: royalties on reprints and merchandising — including film rights — will be given to creators, the first time a major British comics publisher has agreed to do so. ‘2000AD’ No 650 now has colour almost throughout and a strong line-up of stories — including a new-look Rogue Trooper, soon to be a major Warner Bros film. Their new range of graphic novel reprints starts this week with the sumptuously drawn Celtic barbarian fable ‘Slaine’. Altogether, the comics world can break out the bubbly and celebrate its bright future as the cutting edge of art in the ’90s. Or at least it could, until somebody sat on the cake.

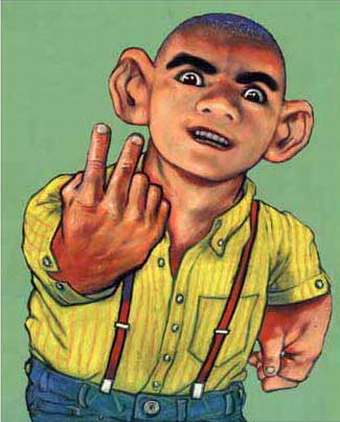

‘Skin’, a new strip that was to run inside ‘Crisis’ and which many considered the standard-bearer for the whole enterprise, was summarily cancelled three weeks before publication. A press release sent out at the time merely states that ‘the market was not yet ready’ for it. But in fact it seems that after their printers refused to print it, the lawyers at Fleetway, the Robert Maxwell-owned publishers of ‘Crisis’, agreed that there might be a danger of prosecution under the Obscene Publications Act as tending to ‘deprave and corrupt’. One can perhaps understand their caution: if Fellini had grown up sniffing glue on a council estate in the ’70s, he might well have created a strip like this. Narrated in a vividly scatological vernacular, ‘Skin’ describes the sexual and intellectual awakening of a teenage thalidomide skinhead, who eventually wreaks a grand-guignol revenge on the drug company responsible for turning him into what his mates call a ‘seal-boy’. Something to offend everyone, in fact; disabled people in particular.

‘I wouldn’t like to offend them,’ counters writer Peter Milligan, who himself was a skin in his teens. ‘I hope that someone reading it would recognise that the thing that offended me, and the thing that really is offensive about it, is the fact that this thing happened, and that they [the German drug company] were allowed to get away with it. So many people just washed their hands of it.’

Ironically, it’s because ‘Skin’ is so well done and has such integrity that it puts people’s backs up. Most political comic strips so far have been worthy manifestos, striking at easy and predictable targets, and at times coming dangerously close to patronising their audience. ‘Skin’s’ moral about greed and lack of accountability in major drugs companies is important, but is never allowed to dominate. This is first and foremost a character study, and of a pretty fucked-up character at that. ‘The reason sex was so prominent,’ says Milligan, ‘was not just for sake of shock, obviously, but because that whole pre-pubescent 14/15/16-year-old thing… all you fucking think about is sex and screwing. At that age — you remember — a few spots and you think “That’s it, I’m never ever going to go to bed with a girl.” And for this guy to have no arms to speak of, you know, this fucking… stigma is going to affect all that stuff. What sort of normal relationship is he going to have? The solicitors at Fleetway didn’t mention it, but I think things like “stink-finger”, references to fingering girls, I think that probably disturbed them. But you know, like, that is what pre-full intercourse is all about. Yeah, but it is a cruel moment when one of the characters says to Martin he’d have to have his face up her arse before he could do that. It’s cruel, but it’s fucking true. And also things like “He looked like a wanker, but he couldn’t even do that.” That’s why sex is very important.

Skin (Milliogan/McCarthy/Swain)

‘At the end of “Skin” it gets less real, goes off into fantasy level, a kind of urban skinhead myth. If there was a sort of skinhead oral storytelling tradition, you know like Beowulf, Homer, that’s what it would be like: “Skin”. The pivotal moment when it changes is one of the moments the Fleetway solicitor objected to. I don’t want to give all the story away, but it involved him going back to this flat with some hippies, and he eats this hash cake and he has a sexual experience, he fucks one of them. And it flips his mind. Things go weird after that.’

Weird is hardly the word; but both this sex scene, when Martin panics and reacts in the only way he knows how — putting the boot in, then scarpering — and the ‘stink-finger’ episode are harrowing and humiliating. That is what gives them the power to disturb, but not, surely, to ‘deprave and corrupt’. If one is going to allocate blame, what of the hundreds of comics in which sex is designed solely to titillate a still largely male young readership, where rape and sexual violence against women are packaged as entertainment, where collectors’ catalogues use the acronym ‘GGA’ — ‘Good Girl Art’ — to describe back issues? Where the cover warning ‘For Adults/Mature Readers Only’ too often signals not something disturbing and challenging, but simply that there is nudity inside? When we are proudly told of the renaissance of ‘adult’ comics, must they all be like the dismal, fellatio-filled ‘Black Kiss’, shrink-wrapped and stacked on the top shelf?

ALLEGORICAL VEGETABLE

But the biggest question must be: if Fleetway’s ‘Crisis’, which boasts of being ‘the cutting edge of British comics’, can’t publish ‘Skin’, who will? It’s a sad indictment of the comics industry that Milligan is currently negotiating with some of the major books publishers, and the prospects there are good. Nor could you imagine them quibbling in the same way as some of the comics publishers who have taken Milligan on. He recalls how DC Comics, America’s biggest, would edit his work during a particularly nervous period: ‘I had to take out all the “shits”, but I could replace them with “crap”. And my characters weren’t allowed to say “Jesus Christ”, but they could say “Oh God” — except for the Irishman, for whom the expletive “Jesus Christ” was considered part of his cultural heritage.’ And a recent cause celebre to rival that of ‘Skin’ was an episode of DCs ‘Swamp Thing’ in which the allegorical vegetable encounters Jesus — that was pulled at the last minute by the publisher.

It’s been a long, hard battle since the ’50s, when the McCarthyite witch-hunts castrated comics and kept them in short pants for the next three decades. Since then, comic shops have been prosecuted; Knockabout comics have been consistently seized at Customs; ‘Action’, which later provided the driving force behind the founding of ‘2000AD’, folded through public pressure in the late 70s. Even magazines have run into difficulty over their support for the medium — several members of The Cuts editorial staff resigned a few months ago over the inclusion of a comic strip, ‘The New Adventures of Adolf Hitler’; and the most recent issue of the trendy arts magazine The Fred was removed last week from the ICA and Royal Academy bookshops, and dropped by its secondary distributor, Central Books, because of a graphic rendering of a rape from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphosis’. Censorship from without and within has been endemic to the comic industry; but somehow, as we approach the ’90s, aficionados may have fondly thought we were beyond all that. The demise of Martin, the thalidomide skinhead, shows that ‘adult’ comics still have a lot of growing up to do.