Richard O’Brien: Rocky Horror? It was all about my mother

Richard O’Brien gave the world The Rocky Horror Show. Now he reveals its secret origins for the first time

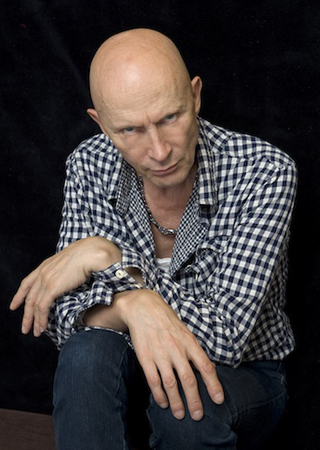

Richard O’Brien dabs at his eyes with a white linen napkin. Somehow the waitress chooses this moment to take our order, and is waved away. We’ve met to discuss O’Brien’s new project, The Stripper, a revival of his 1982 musical, which previously has played only in Australia. Instead, just 20 minutes in, the writer and star of The Rocky Horror Show and host of The Crystal Maze is choked with emotion.

“Not so long ago,” he confides, “I fell off the wagon, stepped into the abyss.” He is small but elegant, like a cashmere jumper washed on too high a heat. His porcelain features, sardonic smile and shaved head strip two decades from his 67 years. And what does he mean exactly, “stepped into the abyss”? “Oh,” O’Brien replies, with a studied attempt at nonchalance, “I went completely crackers.

“All my life,” he explains with mounting emotion, “I’ve been fighting never belonging, never being male or female, and it got to the stage where I couldn’t deal with it any longer. To feel you don’t belong . . . to feel insane . . . to feel perverted and disgusting . . . you go f***ing nuts. If society allowed you to grow up feeling it was normal to be what you are, there wouldn’t be a problem. I don’t think the term ‘transvestite’ or ‘transsexual’ would exist: you’d just be another human being.”

Perhaps this shouldn’t come as such a surprise from the man who wrote the song I’m just a Sweet Transvestite from Transsexual Transylvania, and dressed his entire cast in basques, high heels and fishnet stockings. Yet apart from some elliptical programme notes about being “confined to a life in no man’s land”, O’Brien has never spoken in public of his sexuality. And to find a man of his age and success so confused . . . what happened?

“I’d been fighting, going to therapy, treating what I was as though it were some kind of illness to be cured. But actually, no, I was basically transgender, and just unhappy.” He’s centred enough now to explain the difference calmly: he’s not transsexual, which would mean he felt like a woman, to the extent of wanting an operation to turn him into one; but transgender, which means feeling like neither quite man nor woman. “There is a continuum between male and female,” he says. “Some are hard-wired one way or another, I’m in between. Or a third sex, I could see myself as quite easily.” But at the time, he was not so phlegmatic. “I lost the plot. Paranoid delusions, the works. It was at the time when Bush and Blair ruled the f***ing world, and trying to claw my way back to sanity, I saw no standard norm. I wanted to get back to normal, but where’s the benchmark of sanity? I was drowning and couldn’t find a surface. And then I was talking to my son in Canada, and he told me how much he loved me, how he absolutely . . .”

O’Brien shakes his head in wonder. “It was my children’s love that gave me a centre again. They gave me acceptance of myself, and allowed me to be myself.”

Surely his kids had already guessed that he wasn’t, shall we say, a traditional dad? Even on The Crystal Maze, the Nineties game show that was often Channel 4’s highest rated programme, O’Brien would leap about in skin-tight leather trousers and furry jacket, and speak archly of a backroom figure called “Mumsie”.

“Ha! You’re right!” O’Brien hoots. When he finally plucked up the courage to tell his children he was transgender, their first reaction was: “Dad, and your point is?”

When The Rocky Horror Show opened at the Royal Court Upstairs in 1973, it was joyous, liberating, shocking. A rock’n’roll musical about two clean-cut college sweethearts who spend a life-changing night in a castle with Dr Frank N. Furter and his eccentric retinue, it can be read as an allegory of a drug trip, a paean to (or warning about) sexual experimentation, a love letter to old B-movies, even as a satire on the political degeneracy of America: the 1975 film version, which has repaid its $1 million budget more than a hundredfold, is pointedly set on the night of Nixon’s resignation.

More simply, it’s a contemporary panto that for 35 years has given the audience an excuse to drag up, shout out the best lines, and pelt the screen with bread when Frank calls for “a toast!”. And it’s Frank — dangerously charismatic, thoroughly amoral and joyously polysexual, gloriously played by Tim Curry in the film version and by David Bedella in the forthcoming stage tour — who gives the show its beating heart.

And here a truly surprising thing happens. “He’s a drama queen, really,” O’Brien says of Frank. “He’s a hedonistic, self-indulgent voluptuary, and that’s his downfall. He’s an ego-driven . . . um . . .” and here his voice lowers to a stage whisper, “I was going to say, a bit like my mother.” What was that? Is O’Brien really revealing after all these years that the inspiration for Dr. Frank N. Furter is his mother? This psycho scientist in fishnets who creates a muscle-bound zombie to be his sex toy? Who beds first the innocent Janet and then her straight-as-a-die fiancé Brad? Who seemingly cares for no one and nothing beyond his own gratification? O’Brien’s mum?

“My mother was an unpleasant woman,” O’Brien says with sudden venom. “She came from a working-class family: wonderful people, not much money, undereducated but honest, a great moral centre of honesty and probity. And she disowned them. She wanted to be a lady. And consequently became a person who was racist, anti-Semitic . . . It’s such a tragedy to see someone throwing their lives away on this empty journey, and at the same time believing herself superior to other people.

“I loved her, but stupid, stupid woman, she wouldn’t understand the value of that. She was an emotional bully. And sadly all of us, my siblings and I, are all damaged by this. She was bonkers, my mother, and I think by saying that I’m allowing her to be as horrible as she was without condemning her too much.”

This, it transpires, is the real reason O’Brien’s parents uprooted the family from Gloucestershire when he was 10 to a 120acre farm in New Zealand: so that Mumsie could reinvent herself as posh. Small and effeminate, the young O’Brien was no one’s ideal of Antipodean manhood, and he was routinely caned by teachers. He left school at 15. After five years training as a barber, of all things, he hopped on a boat to London just in time for the Sixties to swing. His breakthrough, ironically, was touring with Hair. The director Jim Sharman then cast him in Jesus Christ Superstar, after which they worked together on a musical O’Brien was calling They Came from Denton High. Sharman suggested the title The Rocky Horror Show, and the rest is hysteria.

If O’Brien ever doubts his legacy he need only remember this: in his home town of Hamilton, New Zealand, there now stands, bigger than life, a bronze statue of himself in his Rocky Horror guise.

And now comes The Stripper, a tale of “blondes, burlesque and bullets” that he adapted from a pulp novel by Carter Brown who, O’Brien says, “never introduced a girl unless he introduced her breasts at the same time”. O’Brien himself will play a cameo. And there’s yet another touring production of The Rocky Horror Show.

O’Brien gets all the devilish parts: the Child Catcher in the recent Chitty Chitty Bang Bang stage show; a one-man cabaret show as Mephistopheles; a corrupt druid in Robin of Sherwood on ITV; an alien in Dark City. You believe him when he says: “I’ve got a really bad temper. I get a few dinosaurs in the street, calling out comments when I’m all dressed up, and I’m like,‘You’re f***ing with the wrong drag addict’.”

Yet he’s a pussycat, really. He’s not currently in a relationship, and says he adores “pottering about” on his own: “You should never go looking for love. One day it will hit you smack in the face.” He’s been married twice, happily, and says of sexual attraction that he doesn’t see the gender, he sees the person.

He’s forgotten, but I first interviewed him more than 20 years ago. He flirted outrageously. “Did I?” he asks, in mock surprise. And as we part this time, no firm handshakes: instead he reaches up and softly strokes my cheek. And then he’s off, through the streets of Soho. In skinny white Armani jeans, a jacket with the shoulders cut off, chunky crosses, and a woman’s wraparound cardigan, he may be still somewhere between male and female, still in that sexual no man’s land. But at long last he’s called a ceasefire.