Boys Keep Swinging

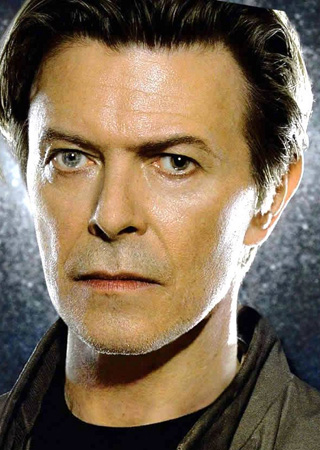

David Bowie: Could I just ask you first, do you mind terribly if we also tape this? Just for our own usage.

David Bowie: Could I just ask you first, do you mind terribly if we also tape this? Just for our own usage.

Dominic Wells: So you can sample me and stick me on your next album?

DB: Actually, it is likely. I nearly sampled Camille Paglia on this album, but she never returned my calls! She kept sending messages through her assistant saying, ‘Is this really David Bowie, and if it is, is it important?’ (laughs), and I just gave up! So I replaced her line with me.

Brian Eno: Sounds pretty much like her.

So: how did this album come about?

DB: A pivotal moment for us was actually at the wedding.

BE: It’s absolutely true, that’s where we first talked about it.

DB: I was just starting the instrumental backings for the ‘Black Tie, White Noise’ album and I had some of them, just as instrumental pieces at the wedding, because it was written half around the idea of the marriage ceremony. Brian at the time was working on ‘Nerve Net’, and we realised that we were suddenly on the same course again.

BE: That was quite interesting, because it was the wedding reception, right, everybody was there, and we started talking and Dave said, ‘You’ve got to listen to this!’ He went up to the DJ and said, ‘No, take that off, play this.’

DB: And then we both rushed off to our individual lives knowing it was almost inevitable we’d be working together again. Because we both felt excited about the fact that neither of us was excited about what was happening in popular music.

It seems strange that on your last album you went back to Nile Rodgers, with whom you had your greatest commercial succcess (‘Let’s Dance’), and now you’re going back to Brian…

BE: With whom you had your least commercial success!

…With whom you had some of your greatest critical successes.

DB: Funnily enough, the things I said to Nile were much the same things that Brian said to me: look, we’re not going to make a stereotypical follow-up to ‘Let’s Dance’. I’d just come out of the Tin Machine period, which was a real freeing exercise for me, and I wanted to experiment on ‘Black Tie’. I love doing a hybrid of Eurocentric Soul, but there were also pieces like ‘Pallas Athena’ and ‘You’ve Been Around’ which played more with ambience and funk. Then there was an interim album for me which was very important – ‘Buddha Of Suburbia’.

BE: That was the one I got really excited about. In fact I wrote you a letter saying this record has been unfairly overlooked. I felt because it was a soundtrack, as usual people were saying, ‘Well it’s not real music then, is it?’ It’s so incredible to me that the critical community is so unbelievably restricted in its terms of reference.

I went to the ‘Warchild’ exhibition at Flowers East [where Eno persuaded dozens of rockstars to auction off their art works for Bosnia], and you made a very good little speech about that. And in fact my magazine was one which had printed a snide, snipy little thing in Sidelines.

BE: Yes, I remember that. Do you, David?

DB: Which snide was this? Ha ha. I’ve had at least a couple in my life.

BE: It was, ‘If these people are so concerned why don’t they give their money over instead of just massaging their already enormous egos.’

DB: I remember that line! Yes, but it’s perfectly understandable. It’s a very British thing, isn’t it? The same’s true in America, isn’t it?

BE: No. You’re allowed to take pleasure in, enjoy and actively even benefit from the act of helping somebody else. Here, if you want to help somebody else it’s got to be directly at your own cost.

DB: It’s got to have a halo attached.

But it’s not just the charity, is it? It’s an assumption that rock musicians shouldn’t be doing art shouldn’t be acting and shouldn’t be writing books.

DB: It’s like saying journalists shouldn’t be doing television shows – which in some cases is probably very true!

BE: In England, the greatest crime is to rise above your station.

DB: There are more and more people moving into areas they’re not trained for, especially in America. I’ve just been doing this film with Julian Schnabel [‘Basquiat’, in which Bowie plays Andy Warhol], and he’s making movies, having just made an album. . . I think that’s fantastic.

What’s the album like?

DB: It’s Leonard Cohen meets Lou Reed. Lyrically, I think it’s really good.

A good dance record then?

DB: Ha ha. I think it’s as good as a lot of other records that came out that week. Not as good as others that came out that week.

BE: One of the reasons it’s possible now is that for various technical reasons, anybody can do anything, pretty much. I can, sitting in my studio, put together records with basses and drums and choirs, or I can put together a video in a similar way. So the question then becomes not, ‘Do I have the skill?’ It’s not an issue.

DB: The skill hasn’t been an issue in art for 50 years. It’s really the idea.

Damien Hirst once said something to the effect that if a child could do what I do, that means I’ve done it very well.

DB: Picasso said, I think, when someone said to him a child of three could do what you’re doing he replied, ‘Yes, you’re right but very few adults.’ I think he said: ‘It took me 16 years to paint like Raphael, but 60 years to learn to paint like a child.’

BE: Einstein said, ‘Any intelligent nine-year-old could understand anything I’ve done; the thing is, he probably wouldn’t understand why it was important.’ That’s the other side of that coin: to be free and simple and child-like, but to be able to understand the implications of that at the same time. To be Picasso is not suddenly to become a three-year-old child again, it’s to become someone who understands what’s important about what the three-year-old child does.

It says in the blurb about your album that much of it was improvised, and that Brian would hand out cards to different musicians saying things like: ‘You are the last survivor of a catastrophic event and you will endeavour to play in such a way as to prevent feelings of loneliness developing within yourself; or: ‘You are a disgruntled member of a South African rock band. Play the notes they won’t allow. ‘ Is that to strip everything down, remove everyone’s preconceptions and start again from scratch?

BE: There are certain immediate dangers to improvisation, and one of them is that everybody coalesces immediately. Everyone starts playing the blues, basically, because it’s the one place where everyone can agree and knows the rules. So in part they were strategies designed to stop the thing becoming over-coherent. The interesting place is not chaos, and it’s not total coherence. It’s somewhere on the cusp of those two.

The rhythm is very strong throughout the album. That’s what holds things together…

DB: Something we really got into on the late-’70s albums was what you could do with a drum kit. The heartbeat of popular music was something we really messed about with.

And very few people had done. It was, ‘Right, bass and drums, get them down, then do all the weird stuff on top.’ To invert that was a new idea. I did a lot of walking around with the album playing on my headphones, and oftenyou would get noises from the street- a bicycle bell, beeps from bus doors – and wherever they came in the songs, whatever noise it was, it fitted right in, you could absorb it into the song and it would work because the layers were so strong you could add anything on top.

DB: The great thing about what Brian was doing through much of the improvisation is we’d have clocks and radios and things near his sampler, and he’d say find a phrase on the French radio and keep throwing it in rhythmically so it became part of the texture. And people would react to that, they’d play in a different way because these strange sounds kept coming back at them.

BE: Yeah, and he was doing the same thing lyrically. We had a thing going where David was improvising lyrics as well; he had books and magazines and bits of newspaper around, and he was just pulling phrases out and putting them together.

DB: If I read some off to you, some of them you’d find completely incomprehensible.

I did try that in fact. I read the lyrics sheet out loud and thought, ‘He’s gone off his rocker.’ Then when I heard it with the music, it made sense.

DB: Exactly. There’s an emotional engine created by the juxtaposition of the musical texture and the lyrics. But that’s probably what art does best: it manifests that which is impossible to articulate.

If an English student, on a poetry course or whatever, sat down and tried to analyse your lyrics, would they be wasting their time?

DB: No, because I think these days there are so many references for them in terms of late twentieth-century writing, from James Joyce to William Burroughs. I come from almost a traditional school now of deconstructing phrases and constructing them again in what is considered a random way. But in that randomness there’s something that we perceive as a reality – that in fact our lives aren’t tidy, that we don’t have tidy beginnings and endings.

So you’d be very happy if I and another journalist had different ideas of what the songs were about?

DB: Absolutely. As Roland Barthes said in the mid ’60s, that was the way interpretation would start to flow. It would begin with society and culture itself. The author becomes really a trigger.

In rock music, the lyrics you hear are sometimes better than they turn out to be. In one of your early songs, ‘Stone Love’, a line I adored was ‘in the bleeding hours of morning’, I finally got the lyrics sheet and discovered it was ‘fleeting hours of morning’, which is much more prosaic.

DB: That’s right. For me the most fascinating thing was finding out after years that what Fats Domino was singing was nothing like… I’d gained so much from those songs by my interpretation of them. Frankly, sometimes it’s a let-down to discover what the artist’s actual intent was.

You’ve now got a computer program, apparently, to randomise your writing. But you’ve been doing cut-ups since the ’70s, inspired by Burroughs.

DB: As a teenager I was fairly traditional in what I read: pompously Nietzsche, and not so pompously Jack Kerouac. And Burroughs. These ‘outside’ people were really the people I wanted to be like. Burroughs, particularly. I derived so much satisfaction from the way he would scramble life, and it no longer felt scrambled reading him. I thought, ‘God, it feels like this, that sense of urgency and danger in everything that you do, this veneer of rationality and absolutism about the way that you live…’

It’s a drugs thing as well, isn’t it? When I was a student and took lots of drugs, suddenly all kinds of things would make sense that otherwise wouldn’t; or rather, you’d see connections between things you otherwise wouldn’t.

BE: That’s what drugs are useful for. Drugs can show you that there are other ways of finding meanings to things. You don’t have to keep taking them, but having had that lesson, to know that you’re capable of doing that, is really worthwhile.

DB: But you know, I think the seeds of all that probably were planted a lot earlier. Think of the surrealists with things like their ‘exquisite corpses’, or James Joyce, who would take whole paragraphs and just with glue stick them in the middle of others, and make up a quilt of writing. It really is the character and the substance of twentieth-century perception, and it’s really starting to matter now.

BE: What I think is happening there is it removes from the artist the responsibility of being the ‘meaner’ – the person who means to say this and is trying to get it over to you – and puts him in the position of being the interpreter.

DB: It’s almost as if things have turned from the beginning of this century where the artist reveals a truth, to the artist revealing the complexity of a question, saying, ‘Here’s the bad news, the question is even more complicated than you thought.’ Often it happens on acid I suppose – if I remember! – you realise the absolute incomprehensible situation that we’re in… (Bowie, who has been gesturing with dangerous animation, knocks an ashtray full of chain-smoked Marlboros on to the carpet) … like this kind of chaos! (Eno kneels to sweep up the ash and butts from Bowie’s feet) Why are you doing that, Brian? That’s immensely big of you.

BE: Just so you can finish your sentence.

DB: I didn’t need to. I illustrated it! (Hilarity) The randomness of the everyday event. If we realised how incredibly complex our situation was, we’d just die of shock.

(There follows a good 20 minutes of discussion about Bosnia, how morality is an outdated concept which should be replaced simply with the law; and how sex and violence are not gratuitous, but forces our human nature compels us to explore.)

There’s a lot in the short story that accompanies your album about artists who indulge in self-mutilation: Chris Burden, who had himself shot, tied up in a bag and thrown on to the highway and then crucified on top of a Volkswagen; Ron Athey, an HIV-positive former heroin addict who pushed a knitting needle repeatedly into his forehead until he wore a crown of blood, then carved patterns with a scalpel into the back of another man and suspended the bloody paper towels on a washing line over the audience. You seem to have this morbid fascination. It’s also the most literal expression of the old idea that art can only come out of suffering.

DB: Also it has something to do with the fact that the complexity of modern systems is so intense that a lot of artists are going back literally into themselves in a physical way, and it has produced a dialogue between the flesh and the mind.

BE: Yes, it’s shocking suddenly to say, in the middle of cyberculture and information networks, ‘I am a piece of meat.’

And is shock also a necessary part of a definition of art?

BE: At some level I think it is, yes. It doesn’t have to be only that kind of shock.

DB: The shock of recognition is actually more what it’s about, you know. I think that’s what it does to me, anyway. That, for me, is Damien [Hirst], of whom I am a very loyal supporter, it’s the shock of recognition with his work that really affects me, and I don’t think even he really knows what it is he’s doing. But what there is in the confrontation between myself and one of his works is a terrible poignancy. There’s a naive ignorance to the poor creatures he’s using. They’re cyphers for man himself. I find it very emotional, his work.

Have you been collaborating with him?

DB: We did some paintings together.We took a big round canvas, about 12-foot, and it’s on a machine that spins it around at about 20 miles an hour, and we stand on the top of step-ladders and throw paint at it.

BE: You should see his studio!

DB: It’s from a child’s game; you drop paint on and centrifugal force pushes the stuff out.

You’re on the editorial board of Modern Painters, along with the likes of Lord Gowrie, and actually they’re not so modern. You must be like the man in the H M Bateman cartoon, saying, ‘Actually, I think Damien Hirst is rather good.’

DB: The magazine is changing. But why write for, say, the Tate magazine, which is full of people already on one side of the argument? At least on Modern Painters there’s a chance of opening up the magazine a little bit. I love the idea of combining some ideas from the Renaissance with ideas that are working now; not to make some kind of . . . editorial point, but because of the pure. . . fun of creating those hybrid situations.

A lot of people were shocked by you doing a wall-paper.

DB: Well, it’s not very original. Robert Gober and a number of others, even Andy Warhol, did them. It’s just part of a tradition.

You also had your first solo art exhibition recently. It must have been frightening to open up your work of 20 years to public scrutiny and to the critics.

DB: No, it wasn’t at all.

Why not?

DB: Because I know why I did it. Ha!

BE: The thing is when you show something, or you release a record, you open it up to all sorts of other interpretations which don’t belong to you any longer. I have millions of tapes at home I haven’t released. I feel quite differently about those than if I put them out on to the market and suddenly there they are, filed in the racks, after the Eagles. Suddenly I imagine someone who isn’t at all sympathetic, who’s actually looking for an Eagles record happening on mine, and I start to hear the thing through what I imagine are their ears as well. So by putting something out you actually enrich it, I think, and you enrich it for yourself. You get it reflected back in a lot of differently shaped mirrors.

DB: I was just a bit late. The reason I wasn’t afraid, either, is I’m an artist, a painter and a sculptor. Why should I be afraid? Seemingly the only other thing I’m supposed to be afraid of is whether other people thought it was any good or not, but I’ve lived that life ever since I began, publicly, of whether I’m any ‘good’ or not, for nearly 30 years, so that comes with the territory.

Does it hurt you if a lot of people are walking around London saying, ‘David Bowie, what a pretentious tosser’?

DB: I don’t know of a time when it was never said, though. What’s the difference? It’s just a different colour overcoat. Not at all.

BE: You know for sure that in England, if you do something different from anything that you did last time, there is going to be a band of people who’ll walk around saying you’re a pretentious tosser but after a while you just have to accept (Bowie is laughing too), both of us just have to accept that we’re good at what we do. The record proves it. We’ve both influenced a lot of things, and a lot of things that are going on can be traced back to what we did, as we would trace ourselves back to other people.

DB: The history of any art form is actually dictated by other artists and who they are influenced by, not by critics. So for me, my vanity is far more interested in what my contemporaries and peers have to say about my work. A lot of it just comes from pure pleasure, you know? I work because it’s such a great way to escape having to work in a shop – to be a songwriter, and a musician and a performer and a painter and a sculptor – it’s so cool to do all this stuff, I can’t tell you how exciting it is. It really is great.

‘Outside’ is released on Sep 26. The first single, ‘The Heart’s Filthy Lesson’, is released on Sep 11.