Christopher Lee: a giant among actors

“If I were to upend this table and smash your face with my stick and plead human rights, you’d see what I mean”

Christopher Lee is late. Not as in “the late Christopher Lee”, thankfully, not yet, though when you break a vertebra and undergo back surgery at 87 that’s always a worrying possibility. But still, half an hour late. Minders are on edge. Calls are made.

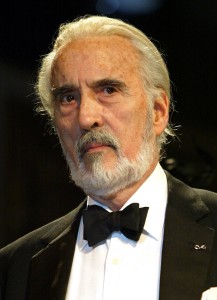

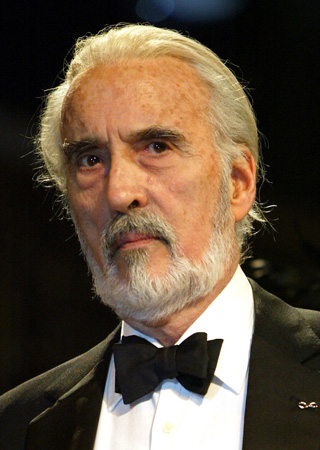

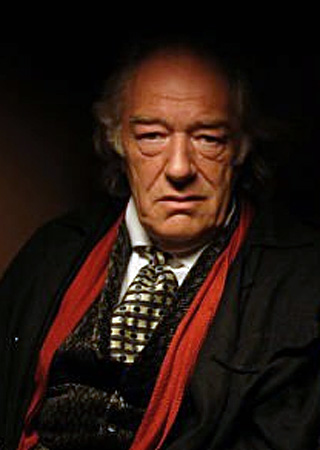

And finally here he is, unfolding his 6ft 5in frame from a black Merc with more than the usual difficulty. He walks haltingly, leaning on his cane. But with his raffish hat, white hair and patrician bearing, you would see that this was a man of distinction even if you didn’t recognise him from his films. Still, why wouldn’t you? He holds the record for the most screen credits, 250-plus, from Dracula and Sherlock Holmes through to a remarkable late flowering in Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings.

“So sorry I’m late,” he intones in the warm bass that nearly made him a professional opera singer. “It’s the Queen, you know.” The Queen’s Speech. Many London streets have closed. Having been knighted only two weeks ago, Sir Christopher can hardly complain.

We edge towards the National Portrait Gallery, where Lee later has a lunch date. He refuses painkillers because, he says, catch 22, they affect your balance. How did he bend down to be knighted if his back is so bad? “I couldn’t!” he reveals. “And also they have this platform for you to stand on, no bigger than a square tile. Well I had to tell Prince Charles’s equerry I didn’t think I could do it.”

At the restaurant entrance, while fumbling with his coat, he drops his stick. “The story of my life,” he deadpans. “Either my stick falls down or I do.”

An athlete who does his own stunts, Lee has often injured himself for art. He was thrown from a chariot in Quo Vadis; cracked three ribs in The Mummy when breaking down a door that had accidentally been locked for real; crashed a car after filming Battle of the V-1. He stumbled around, still in his SS uniform, terrifying the residents of Hove. He holds the record for the most screen swordfights. He raises a crooked little finger. Broken by Errol Flynn, apparently. “After lunch.” He cocks a single bushy brow. “A long lunch.”

This latest back injury was less spectacular. He tripped over two small cables while working on a new Hammer horror picture in New Mexico. The company that made Lee’s name (or was it the other way around?) has been resurrected by John De Mol, the founder of the media giant behind Big Brother. The double Oscar-winner Hilary Swank plays the lead, which gives some idea of the stakes (sorry) this time round. How does it feel to come back full circle? “It is ironic, isn’t it?” says Lee. “And I am one of only a handful of actors from that period, 50 years ago, to survive.”

Descended from an aristocratic Italian family, Lee honed his elocution, deportment, breathing and fencing at the Rank Charm School. A literate and thoughtful actor, he invests even villains with a depth and a quiet dignity in what he refers to as their “loneliness of evil”. He researches parts meticulously, fighting with directors over authenticity: his SS officers wear grey, not black; his Dracula dresses all in black as Bram Stoker intended, with no flashy red.

But it’s a fight he can never win. Recently he filmed Season of the Witch in Budapest with Nicolas Cage. “I was a cardinal who had contracted the plague,” he explains, “so you can imagine what I looked like! But I got to spend the five days filming in bed, which was very nice.” He was glad to see they had a language expert on set to advise the film-makers, until he got his instructions: his Italian cardinal was to be played with an American accent.

Lee has nothing but warmth for Cage, bearing no grudges for his misguided remake of The Wicker Man, the 1973 chiller that until The Lord of the Rings was Lee’s favourite of his long career. In fact, Lee is also making a new film with the original Wicker Man director, Robin Hardy. It’s not actually a sequel, Lee reveals, despite being called The Wicker Tree. He is also logging his fifth collaboration with Tim Burton, as the voice of the Jabberwock in Alice in Wonderland.

But the film closest to his heart is Glorious 39. Stephen Poliakoff’s latest historical thriller takes Lee back 70 years, to the start of the Second World War. It is set among the appeasers who believed that war would destroy England, and that striking a deal with Hitler was the only way to survive. Of the stellar cast, which includes Bill Nighy, Julie Christie, David Tennant and Jenny Agutter, Lee is the only one who was actually there.

“See now,” he says, “I remember so well. I was 17, working as an office boy for £1 a week, and I could see what was happening. After the Munich Agreement in ’38, lots of people breathed a sigh of relief, but I was old enough to know what was going on, I’d seen the parades. I remember telling my mother and my sister: ‘I don’t know about this wonderful news about peace in our time, I don’t believe it’.”

He enlisted two years later. By the age of 21 he was working as an intelligence officer, daily holding the life of thousands in his hands. He left this period out of his autobiography, Lord of Misrule. “Just because one was involved in certain operations,” he says, with typical self-effacement, “it looks as though you are saying ‘I did it’. But really it’s ‘we’.” Much of his service in North Africa was, in a strange kind of way, fun. He was nicknamed Duke, or Spy. Senior Air Force officers were called things such as Oswald Gayford and had huge handlebar moustaches. You could end up on planes to places “just like hitching a ride”.

But the end of the war was anything but fun. Because he was fluent in French and German (among other languages), he was attached to the Central Registry of War Criminals. Along with representatives of other nations, he became a Nazi hunter.

“We were given dossiers of what they’d done and told to find them, interrogate them as much as we could and hand them over to the appropriate authority. In view of the fact that there were Palestinians with us, which simply means Jews, because of course Israel was not its own country until 1948, you can imagine how they felt. We saw these concentration camps. Some had been cleaned up. Some had not.”

Lee looks away. He has no wish to project such visions on to the screen of memory, much less talk about them. But in an age when the BNP’s Nick Griffin, a man who once denied the Holocaust, can end up on Question Time, is it not important to bear witness?

“It’s not possible to deny it,” Lee says. “You can’t fake an entire camp with dying people. You can’t. Like when you see a film, even if it’s a good film, you can’t expect the camps to be accurate, for actors to look like they would really look, like they were dying. You can only go so far.”

The pain in his eyes is real, and you get a glimpse into what might animate the lonely tortured creatures he creates so effectively on screen. The doomy romanticism of his Dracula made it the surprise smash of 1958, the Twilight of its day. Five decades later, as the human face of evil in The Lord of the Rings, he proved himself the only actor on the planet able to out-thesp Ian McKellen.

Once, just once, he allows a flash of this fire to enter his otherwise unfailingly courteous conversation. We are discussing politics. Lee is staunchly Tory, a David Cameron fan. “It’s a question of ideas. And he has them. I like William Hague, too, he makes the best speeches.” He believes in stronger immigration controls. “This country is bursting at the seams. That’s not a racist position, simply that there are too many people in a small country, and that results in increased crime.”

But it’s on Europe that he feels strongest. “I’m not in favour, no. Each nation should have its own laws, its own government, its own culture. I don’t think you can create a vast melting pot. And for an unelected president to be able to tell everyone what to do, no matter who it is, is a complete disaster.

“To me, the worst thing about the European Parliament is the question of human rights. We should have our own bill of rights. I don’t want one man deciding whatever you can and can’t do. I mean if,” and here his eyes take on a peculiar intensity as if seriously contemplating such a course of action, “if I were to upend this table and smash your face with my stick and plead human rights — you see what I mean.”

Not entirely, but it would take a brave man to argue the point, bad back or no. Besides, Lee is late for his lunch guests. They are veterans, too, Special Forces, sitting tweed-jacketed in the panoramic Portrait Gallery restaurant, eye-to-eye with Nelson’s stone buttocks. Lee introduces himself, all smiles, his body language strangely deferential. Sixty years of achievement and awards melt away: it’s what you did in the war that counts.

Watching him, you are reminded of his story about playing Jinnah in 1998. Leaving aside ethnic origin, the founder of Pakistan looked remarkably like Lee. “But,” Lee says, “one person did complain to me: ‘Jinnah wasn’t as tall as you’. So I replied: ‘Maybe not, but he was a giant’.”

Once there were giants in British film, too. Sir Christopher Lee is one of the last of his kind. Long may he tower above us.