Moore the merrier

Dominic Wells meets the graphic writer Alan Moore, probably the sanest man ever to worship a snake god

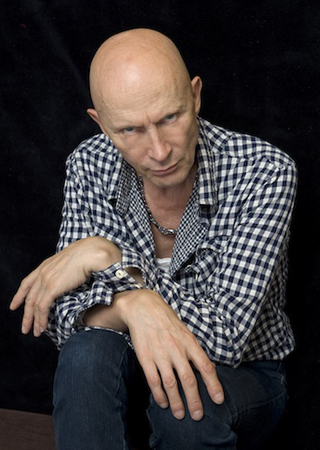

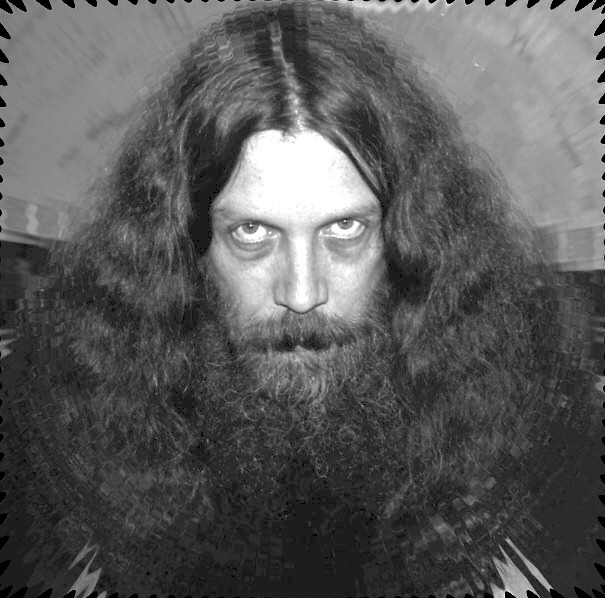

Alan Moore

“I CONTINUALLY monitor the possibility that I might be going mad,” said Alan Moore on publication of his first “proper” novel six years ago, after a decade as the world’s most successful writer of graphic novels.

Reminded of this now, Moore chuckles into his beard: “Oh, I’ve gone much madder in the last six years, though my ideas have become more sophisticated. Yes, I was a mere amateur in lunacy then …”

If an author tells you that he has become a magician (think Aleister Crowley rather than Paul Daniels) and is worshipping a second-century Roman snake God, you do begin to wonder about his state of mind. But no one could question Moore’s success. Seldom straying from his home in Northampton, he works on eight comic titles at once; his Jack the Ripper saga From Hell was turned into a movie starring Johnny Depp; his latest, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, is now filming, with Sean Connery heading a £60 million production.

This last began when Moore, who redefined the superhero genre in 1986 with Watchmen, was struck by its 19th century roots: Dr Jekyll/Mr Hyde was clearly the model for The Incredible Hulk, while The Invisible Man could have joined The Fantastic Four. He conceived of a team of heroes in an alternate Victorian universe in which those two fought alongside Alan Quatermain (from King Solomon’s Mines), Captain Nemo (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea) and Mina Harker (Dracula), with the film version adding a grown-up Tom Sawyer for American audiences. “There was a point in the first issue when I had just had Zola’s Nana murdered by Stevenson’s Hyde on Poe’s Rue Morgue when I realised just how much fun it could be pulling down the picket fences between various fictional realities.”

So ripping a yarn indeed, that a producer sold it to 20th Century Fox on the premise alone, before a word had been written. Moore’s black humour is unlikely to survive the transition to celluloid, so do not expect to see Connery playing Quatermain as an ineffectual junkie, nor the Invisible Man living it up as the “Holy Spirit” to a dormitory full of miraculously pregnant young girls. And as always with Moore, there are layers within layers to which a film cannot begin to do justice.

While the question “where do your ideas come from?” gets short shrift from most authors, to Moore it is “the only question worth asking.” Six years ago he was toying with the notion of “Idea Space”, a literal pool of shared concepts into which a correctly attuned artist could dip. Now he is beginning to map it.

“This planet has a physical geography with which we have already familiarised ourselves. But since the dawn of the first stories, there is a fictional geography, where the gods and demons live. We have created this big imaginary planet that is a counterpart to our own; and in some cases these places are more familiar to us than the real ones.”

Moore is intrigued by the notion that stories, and past events, can leave a physical trace. His insanely ambitious 1996 novel, Voice of the Fire, was contained geographically within a ten-mile radius of Northampton, with each chapter set in a different century, from Stone Age to present, and each written in a style suited to the time. It so happened that the final chapter featured a dog trotting about with a decapitated head in its jaws; eerily, soon after he wrote that passage, this actually occurred near by. At the time he wondered whether he had intuited the future event, or somehow willed it into existence (coincidence does not seem an option). What does he believe now? “Probably both. Ultimately I couldn’t say. I don’t think time is as we see it, and that means cause and effect are different from the way we see it.”

Moore can discourse at length on the convergence of modern scientific beliefs and ancient intuitions. In the end, he believes, magic is simply the creation of something out of nothing: be it rabbits from a hat, a plot idea from a blank sheet of paper — or the universe from a quantum vacuum. But it is also about individuality: he has no desire to convert anyone else to so “manifestly preposterous” a practice as worshipping a snake god. As an anarchist, a political persuasion that he stresses is simply about taking personal responsibility, he equates organised religion with fascism — both involve abandoning your personal responsibility to the group.

Add to this his penchant for getting together with other like-minded souls to perform magical music and rituals — to some critical acclaim, in the case of his channelling of Blake at the Tate Britain last year — and you have not just one of the most singular creative minds around, but also a close candidate for Britain’s most embarrassing dad.

“Only as much as they embarrass me,” he quips when asked what his daughters make of it all. “No, we get on great, I’m immensely proud of them. Leah, who’s 24, has just started some comic writing. Amber, who’s 21, just finished her computer studies degree and is now working as a bouncer in Hull.”

So she must have inherited the imposing paternal stature? “That, and lots of piercings and tattoos. And some entirely gratuitous spiral white contact lenses. I have no tattoos of my own, but unlike Ozzy Osbourne, have no problem with my daughters getting them.”

Alan Moore

He may dress like a roadie discovered during a rock band’s tour of the Himalayan snowline, but Moore is a softie really: considerate, soft-spoken, preternaturally articulate. Not one’s stereotype of a practitioner of the Arcane Arts. “I’m with Austin Osman Spare,” says Moore. “When people asked him if he was a black or a white magician, he replied: ‘Magic is colourful’. There is a Satanism in which heavy metal bands looked for darkness, for cheap notoriety. My involvement with the occult is not about darkness, but about illumination. “I don’t sacrifice many goats,” adds Moore, wryly. “As a vegetarian, that would feel kind of wrong.”

Moore is exploring some of these themes in a comic series called Promethea, and hopes soon to expand on them in book form — without the drawings, that is. Comics, it transpires, are only his second-favourite art form: literature is his first love, current reads being Donna Tartt, Tom Spanbauer, Michel Chabon and his friend Iain Sinclair. The cinema does not even make his top five.

“Literature is the highest possible technology,” he enthuses. “It’s virtual reality right there: 26 letters rearranged in certain forms which, when decoded by the average human mind, can recreate a complete wraparound 3-D environment.” Sadly, however, it does not pay the rent. Voice of the Fire earned him just £15,000 for five years’ work. Comics are a little more lucrative, especially with the movie deals thrown in (“The Invisible Man doll is the piece of merchandising we’re really going to make a profit with,” he deadpans).

One reason for his tremendous work rate is so that he can be in a position to semi-retire in a year, and write only what pleases him. He will be 50 years old. In the meantime, he continues to get some of his incredible ideas from the snake god Glycon, and some from a couple of other gods, such as Mercury, who he speaks to at times. He is not remotely fussed about whether anyone else buys into this as reality, reality being overrated anyway, but this is his take on reality, and it produces results. And can you offer a more sensible explanation for that flash of inspiration that seems to come from nowhere?